Glued lapstrake boats are built using plywood for planking, and laminated wood for structural parts like the stem, keel, etc. All held together by that boon to amateur boatbuilders: epoxy.

As expensive as marine plywood is, it's not hard to find, and you don't really need to know that much about the wood inside the plywood. If you buy certified marine plywood, you can leave all the wood knowledge to the experts. They will choose the right type wood, grade it to ensure quality, and glue it up properly.

Plywood is not wood, so much as it is an industrial 'material'. And that makes it reliable, consistent, and relatively easy to understand and work with. I would not have finished Cabin Boy so quickly without it.

On the other hand, wood -- real wood -- is complicated stuff. It comes in a dizzying number of species and subspecies, each with a slightly different set of properties. Someone once said there is such a variety of wood, that it is possible to find a wood with the perfect set of properties for any conceivable application. Because of modern transportation systems, it's possible to buy a much larger variety of wood that was ever available to our boatbuilding forefathers. Paradoxically, the old growth wood that our ancestors took for granted (and used in such profligate amounts), are for all intents and purposes, difficult or impossible to find.

Olde time boatbuilders in Maine, say, depended on a relative handful of woods that were inexpensive, easy to obtain, and locally grown. Builders got to know those woods intimately, first from their experienced teachers (i.e., the builder they apprenticed with), and then through long use. Their knowledge of wood wasn't wide, but it was deep. Uproot a Maine boatbuilder of the 1800s and move him to the Pacific Northwest, and he'd have a whole lot of learning to do, before he was comfortable with the new set of trees he had to work with.

Amateur boatbuilders of today are in a triple pickle. Compared with the olde time boatbuilders, their experience is rarely wide or deep; many of the species recommended by classic boatbuilding texts are difficult to find; and it's hard to know which of the many 'exotic' species available in specialty lumber yards would be the best replacement.

To compound the problem, professional boat builders, who presumably do know a lot about wood, are as rare as old growth forests. Unless you live in one of the few communities where boatbuilding is still alive, you can't just walk down to your local boatshop and ask someone with 40 years experience.

No wonder so many boatbuilders throw up their hands and use plywood!

That isn't an option for my boomkin, though. I need to use a wood that's both super strong and easy to bend. Tom Gilmer specified hickory for the boomkin. When I first started asking around about hickory, I got conflicting advice.

The sales guy at the premier wood boutique in this neck of the woods told me flat out that hickory wasn't used on boats. Period.

Online, people told me that hickory was super strong, but probably wasn't very good for steam bending. At least, they'd never heard of it being used for bending. That got me thinking about cutting up my lumber into thinner strips, and laminating, but I really wanted to try steam bending, so couldn't give up without doing a bit of independent research.

So I was pleasantly surprised to read this in Howard Chapelle's classic text, "Boatbuilding":

"There are a number of matters that deserve attention, however. First, the woods that respond to steaming and boiling; these are generally hardwoods. Where the curvature is to be very great, rock elm, ash, and hickory (true and pecan) are the best, as they withstand great deformation. Less extreme bends can be made with white oak, beech, birch, maple, and red gum. Douglas fir and yellow pine can only be steamed or boiled to very slight curves."

I was able to confirm hickory's bending qualities by consulting my new 'bible', the US Department of Agriculture's "Wood Handbook". This thick tome is packed full of technical details that you can trust. The problem is finding or understanding what you need to know, but I'm making slow progress.

So, I guess old Tom Gilmer knew what he was doing when he specified hickory.

Anyway, my steam bending plans are back on, and I'm proceeding ahead at full speed. First up, build a steam box!

Like all steam box builders, it seems, I wanted to spend as little money as possible on mine, yet end up with a box that could be used for many future projects. Cheap pine is a good material, because it's... well, cheap, and also because pine doesn't bend much when steamed. You wouldn't want to build your steam box out of hickory, for example.

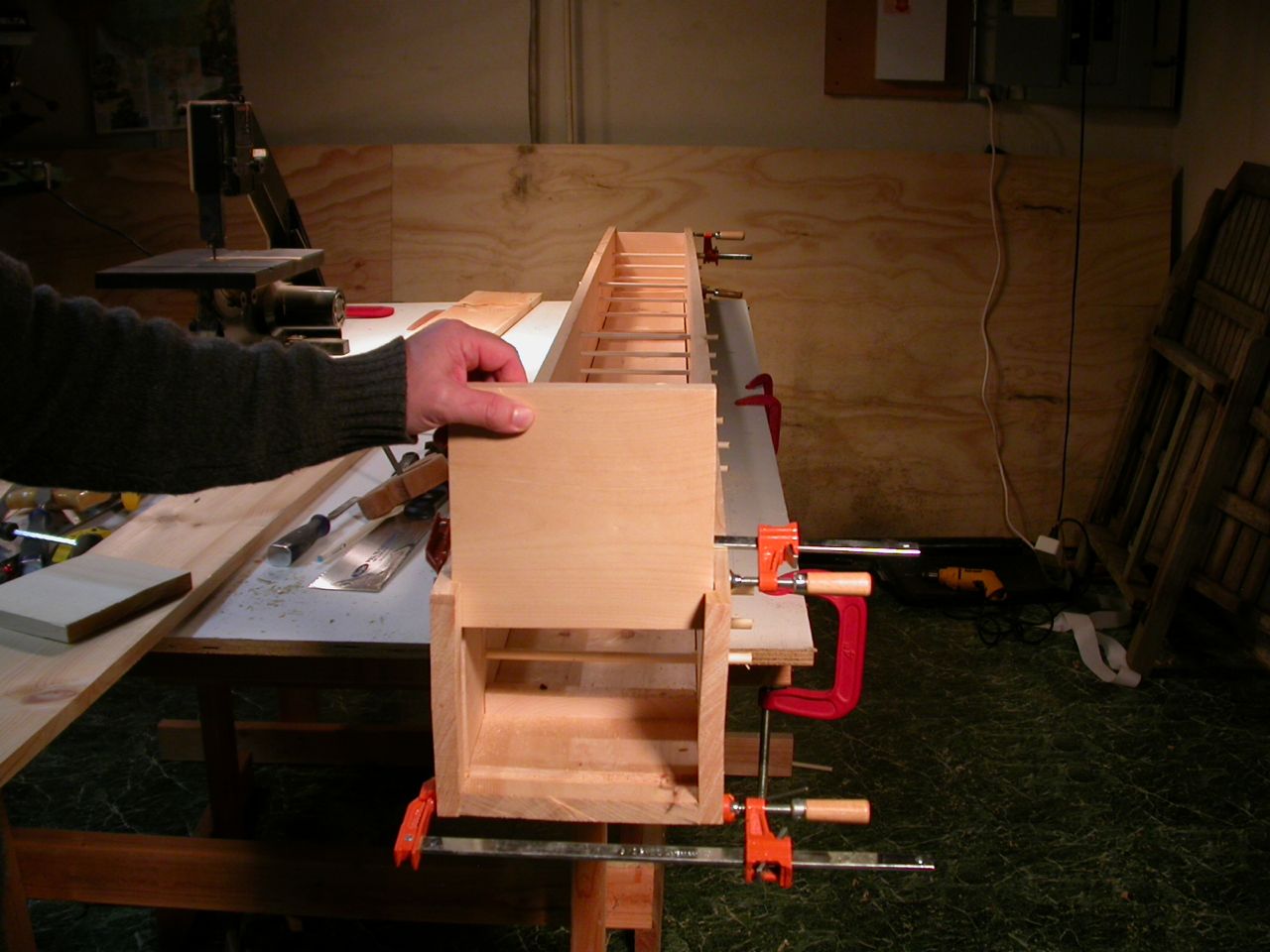

I wanted to be able to stack wood on several levels, inside the box, so I drilled holes in the side for three sets of removable 'pegs', and added cleats on the bottom, to keep wood elevated off the bottom of the box.

|

| Holes drilled in the sides for removable pegs, cleats on the bottom. |

I also wanted a door that was easy to open and close. I've been fooling around with basic joinery, lately, and have recently built a homemade router plane. So it seemed like a good idea to use dado joints for both the closed (non-opening) end of the box, as well as for a sliding door on the opening end.

|

| Cutting the 'sides' of the dado with a saw |

I did it by cutting the 'sides' of the dado with a handsaw (above), and then chiseling most of the waste out of the dado with a chisel.

Then I used my router plane to finish the dado. This is not a very good picture, but underneath the plane is a narrow, 'L' shaped blade that essentially scrapes the bottom of the dado smooth.

The blade is made out of a hex wrench that I ground into a blade and sharpened. It took a bit of work to do this on my hand-turned grinding wheel, but there was no risk of loosing the temper in the steel. It works like a charm!

|

| Home made router plane and stopped dado. Knots just make the job more fun! |

At any rate, with a bit of care and elbow grease, you end up with a pretty nice dado.

|

| End board dado'ed into bottom board. |

Skipping ahead a few steps, this is what the box looks like with the pegs installed, and everything held together by clamps, for a trial assembly. Obviously, the top is not installed.

|

| Trial assembly, looking at opening end |

This is the opening end. And this is how easy it will be to open.

|

| Ta-da! |

And this is what it will look like, more or less, with the top on.

|

| With top on |

But before I can screw the whole thing together, I must install some sort of fitting in the bottom, so that I can easily attach the steam hose. I plan to use a radiator hose.

So next time, we'll look at the 'plumbing' that goes into my steam box.

Can't wait to fire it up and get some hands on experience with steaming wood.

>>> Next Episode: Steambox Boiler

John: Pine may not bend much when it's wet or steamed, but it sure will swell. You could find your dadoed door slides swolen tight if your fit is too close.

ReplyDeleteI enjoy your blog posts immensely. Thanks for the thought and work you put into the blogwork. John in Augusta

Yes, I thought of that, so made the door fairly loose fitting. I would hate to have my lumber trapped inside and over cooked!

ReplyDeleteI like the router!

ReplyDeleteCan't wait to see the results.

ReplyDeleteSaw a very primitive "steambox" in a small Mediterranean boat yard once. A long piece of very wet, unidentifiable wood was placed in the downspout of a gutter on a shed roof and a small wood fire lit at the open end of the base of the downspout. I presume the upper end of the downspout was plugged with a rag - more of a warm wet box than a steambox.